Protecting Indoor Environments from Wildfire Smoke

Over the past two decades, protecting indoor environments from wildfire smoke has become a greater concern for building owners and occupants. Wildfires have increased in size, frequency, and intensity worldwide, especially in the western United States. Research shows that the ongoing and persistent effects of climate change are a primary driver, contributing to longer fire seasons, more frequent events, and larger burned areas. As a result, wildfire smoke has become a serious concern for building owners and occupants, with air quality impacts often extending far beyond the areas directly affected by fire.

Understanding Wildfire Smoke

As anyone who has experienced wildfire season can attest, smoke can immediately affect your eyes and respiratory system. However, there are also long-term concerns related to cardiovascular and lung disease. Wildfire smoke can enter a building through the building openings in the form of natural ventilation and infiltration and through the HVAC mechanical ventilation systems.

While wildfire smoke is comprised of many gaseous pollutants harmful to humans and the environment, the particulate matter (PM) found in wildfire smoke is the primary public health threat. It is almost always the dominant pollutant driving the Air Quality Index (AQI) score on smoky days.

Particulate matter consists of solid particles and liquid droplets suspended in the air at the microscopic level. Human hair measures approximately 50 microns in diameter, while wildfire particulates are in the range of 2.5 to 10 microns. Particles with diameters less than 10 microns (PM10) irritate the upper respiratory tract and eyes. However, smaller particles (PM2.5) can be inhaled deep into the lungs and may even enter the bloodstream. Our primary concern as building designers is how to prevent these particles from reaching the occupants.

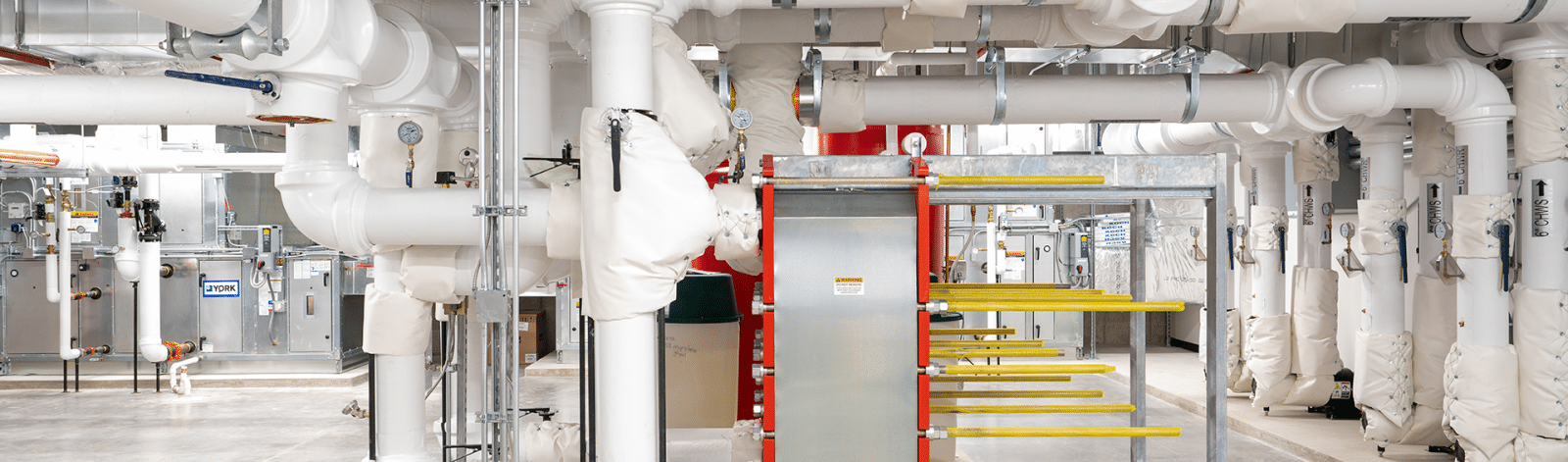

Designing New HVAC Systems to Reduce Smoke Effects

When designing new buildings in wildfire-prone regions, it is best to address mitigation strategies for smoke exposure early in the design process. Depending on the building’s mechanical system, there are many different implementation strategies, based on current technology, the availability of facilities staff, and the building owner’s budget.

Buildings using centralized air handlers or direct ventilation at zone-level fan coils or furnaces should be designed to accommodate both MERV 8 pre-filters and MERV 13 final filters. It is essential to review the fan curves for these HVAC units and ensure the added pressure drop from a dirty MERV 13 filter will not create a demonstrable decline in performance.

For buildings served by all-water or variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems, filtration must occur in the Dedicated Outdoor Air System (DOAS), as zone-level equipment often cannot accommodate MERV 13 filters. These distributed systems typically lack sufficient fan power and filtration space to provide meaningful particle removal.

Designers should also include manual overrides or automated controls, such as PM2.5 sensors, to disable economizers and demand-control ventilation (DCV) systems during smoke events. These systems, which typically bring in large quantities of outdoor air to reduce cooling loads or manage CO₂ levels, can introduce harmful smoke if not appropriately managed. These unique control strategies should be thoroughly documented in the operations and maintenance (O&M) manual and included in owner training at project turnover.

In buildings designed for vulnerable populations—such as schools, daycares, senior care, and healthcare facilities—HEPA filtration should be considered for additional protection. These high-efficiency filters can remove over 99% of airborne particles greater than 0.3 microns. Still, they should exclusively be used in equipment with custom fan motor selections that can handle the associated pressure drop.

Architectural strategies also play a role in smoke mitigation design. Vestibules should be incorporated at building entrances and located away from prevailing winds. Air curtains can be useful in specific applications, such as loading docks, but they should not be used as vestibule replacements in wildfire-prone regions.

Buildings should also avoid solely relying on natural ventilation strategies, as the uncontrolled introduction of outdoor air during smoke events can significantly compromise indoor air quality. Instead, hybrid ventilation approaches that allow for full mechanical isolation when needed are preferred.

New HVAC System Design Highlights:

- Use MERV 8 pre-filters and MERV 13 final filters where possible.

- Check HVAC fan capacity to handle MERV 13 pressure drop.

- Filter outdoor air at the DOAS in VRF or all-water systems.

- Install PM2.5 sensors to disable economizers and DCV during smoke events.

- Use HEPA filters in buildings for vulnerable populations (with proper fan design).

- Avoid using air curtains as vestibule substitutes.

- Don’t rely solely on natural ventilation; use hybrid systems for smoke control.

Updating Existing HVAC Systems

In existing buildings, financial and operational constraints can limit the extent of improvements, but meaningful action can still be taken to protect occupants. The simplest and most immediate step during high smoke events is to temporarily shut down outdoor air ventilation. However, this must be done carefully, as completely shutting off outdoor air can cause negative pressure from exhaust fans, leading to unintentional air infiltration through leaks in the building envelope. It is recommended to maintain a slightly positive building pressure—typically between 0.02 and 0.07 inches of water column—by ensuring the building has roughly 10% more outdoor air than exhaust.

If system performance allows, temporarily upgrading outdoor air filters to MERV 13 during wildfire season is an effective strategy. While these filters do increase pressure drop, many systems are capable of operating at reduced flow with high-efficiency filtration. For example, a system designed for 100% economizer cooling could have a MERV 13 filter installed on the outside airstream and operate at ventilation airflows without generating a significant pressure drop. To confirm compatibility, a mechanical engineer should evaluate the fan system and its specific configuration.

Similarly, involving a commissioning or energy professional to perform a blower door test or building envelope assessment can help identify and seal leakage points that allow smoke infiltration. Outdoor air dampers should be inspected to confirm they operate correctly and form a tight seal when closed. Retrofit filter racks should be factory-assembled, not field-fabricated, to ensure outdoor air passes through the filter rather than bypassing it.

In buildings that lack mechanical ventilation systems altogether, portable air cleaners (PACs) are a viable solution. These devices recirculate indoor air through a combination of pre-filters and HEPA filters. During wildfire events, they should operate continuously. Larger areas will require multiple units to achieve sufficient air turnover.

While portable cleaners are useful, considerations around noise, energy use, and storage must be factored into operational planning. Many of these systems also include activated carbon filters to reduce smoke odors, but it’s important to understand that carbon does not capture particulate matter and is not a substitute for MERV-rated filters.

Updating Existing HVAC Systems Highlights:

- Temporarily reduce or shut off outdoor air during smoke events but maintain a slight positive pressure (0.02–0.07 in. w.c.).

- Upgrade to MERV 13 filters during wildfire season if the system can handle the added pressure drop.

- Identify and seal leakage points with a blower door test or envelope assessment.

- Ensure outside air dampers operate properly and seal tightly.

- Use factory-assembled filter racks to avoid air bypassing around filters.

- HEPA-equipped portable air cleaners (PACs) are a viable option in buildings without ducted mechanical ventilation systems.

Ultimately, whether designing a new building or improving an existing one, the goal remains the same: to create indoor environments that protect occupants from the health hazards of wildfire smoke. Through thoughtful design, strategic retrofits, and careful operation, buildings can serve as effective barriers against poor outdoor air quality and provide much-needed refuge during wildfire events.

Contact us for more information