Town of Plains Wastewater Treatment Plant Relocation

Escaping an Encroaching River

The Town of Plains had a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) that was functioning well, meeting their discharge permit, and had been upgraded within the last ten years. Under normal circumstances, no one would recommend doing anything other than what the town’s plant operators had been doing for several years. But the nearby Clark Fork River had other ideas.

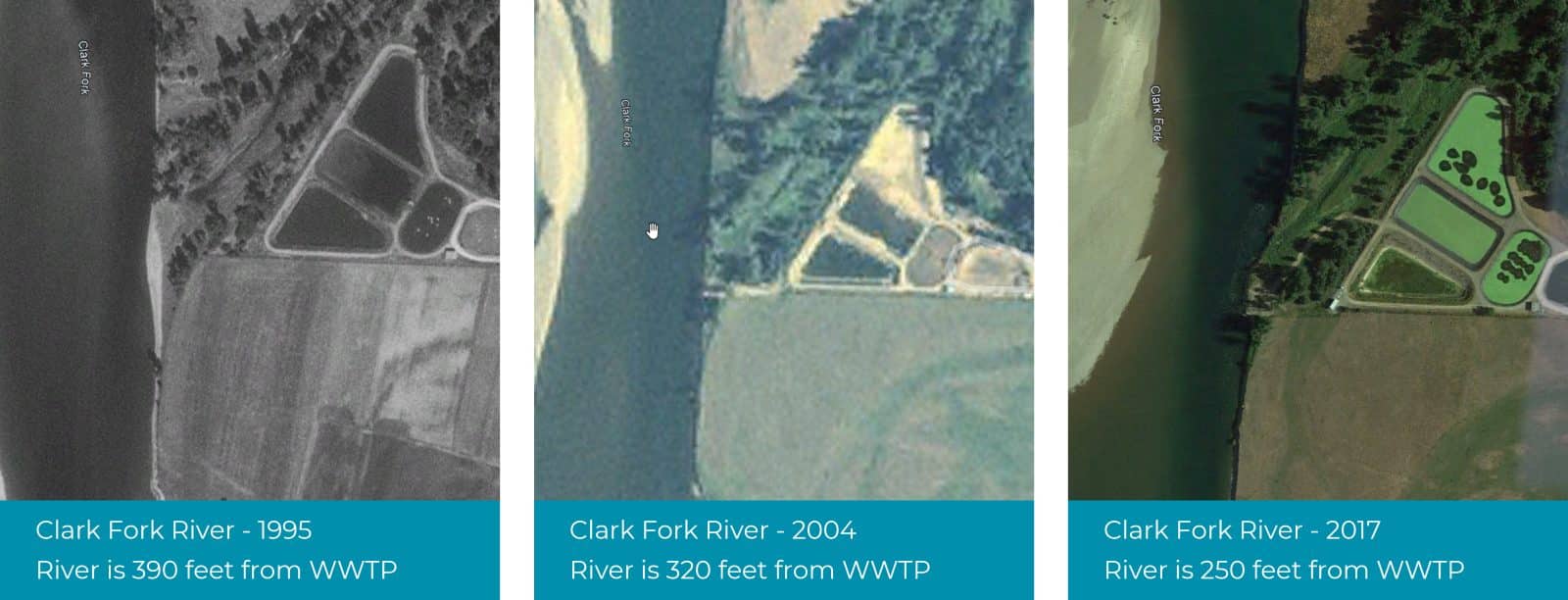

Several flood events led to the river moving toward the WWTP. From 1995 to 2017, the river moved from 390 feet away from the plant to 250 feet. The Army Corps of Engineers tried installing rip rap on the banks of the river, but after a flood occurred and eroded more banks, the town needed to do something to protect this piece of critical infrastructure.

After several preliminary engineering reports and updates, Plains settled on relocating the facility and designed and constructed an entirely new plant in a new area away from the Clark Fork.

Services and Highlights

-

Closeout services

-

Construction administration

-

Construction observation

-

Design

-

Prime consultant

-

Startup service

All Under One Roof

The goal was to design a compact facility that was easy to operate and had all the equipment in one building versus their current plant, where key pieces of equipment were located in various buildings and locations within the plant. This would benefit the operators because it provides a single location so they can check on equipment, keep records, and perform daily operational duties.

The new facility included a headworks, something the previous WWTP didn’t have. The town wanted this to help keep the garbage (i.e., plastics and non-organic materials) out of the treatment basins. The headworks include a screen that sits high enough so the water can flow through the aerated lagoons without pumping.

Air used for aeration of the lagoon basins is supplied by high-efficiency blowers housed in the same building. The blowers have sound enclosures that provide excellent noise reduction, and you can hold a conversation while standing next to them.

The flow continues through a UV disinfection facility from the far end of the lagoon basins. Since the influent screen and the UV disinfection process are in the same building, the UV facility must be much lower than the screen so the water can flow downhill. This layout was possible because the project was a “greenfield” plant, and the site, piping, and building elevations could be laid out to accommodate the single-building concept.

The building also has space for other auxiliary equipment, like a non-potable water facility that supplies water to wash the screen, hose bibs for washing down water in and around the building, and a shower. Lastly, the building includes an office, bathroom, shower, and adjacent electrical room to create an efficient working space for the plant staff. The WWTP will house the Town’s SCADA system for the wastewater and water system.

Designed for Efficiency and Location

Morrison-Maierle worked with the operator to make equipment selections they were comfortable with. For example, the UV system is a non-contact system that’s easy to clean. Typically, the UV system sits in the channel, and the flow goes past the bulbs (which are expensive) and needs to be cleaned often. The bulb enclosures are made of quartz and can break easily.

What’s unique to Plains’ new design is that the Town selected a UV system that uses 10 tubes (think straws) to convey the water, and the bulbs sit outside tubes. The advantage is that the operators don’t have to raise and lower the bulbs for cleaning but instead run a large pipe cleaner through the tubes, which creates less wear and tear on the bulbs and ballast.

Selecting equipment early enabled Plains to get the best product for the project instead of waiting until the end, when the contractor may have chosen based on price rather than functionality and operating costs. This happens frequently to smaller communities that have to stretch their project dollars further, leaving them with equipment that may cost more to maintain and operate. This also burdens them because grant funding gets used quickly for construction and then is gone when power bills become due.

The Town of Plains Wastewater Treatment Plant Relocation project fitted a lagoon system into an existing agricultural landscape, sized it for the community, and made it maintenance- and operator-friendly in a space next to a residential development area and an airport.

To conceal the water’s surface from nearby traffic, the berms of the lagoon are raised above the surrounding ground so that the water’s surface can’t be seen from the road. A 3D rendering was presented to show the view from the second story of hypothetical houses within the development to show the town how this would work. The building’s exterior finish matches the surrounding rural buildings to blend into the landscape.

Blowers are the highest energy users in treatment facilities. The blowers in the old facility did not have variable frequency drives (VFDs), and operators had no means to adjust airflow. The new blowers have VFDs and can adjust total airflow to only what’s needed. The VFDs save energy when lower air demands are required while providing the flexibility to turn airflow up if the process demands it. Preliminary calculations showed that the energy savings could pay back the higher capital costs within 5 to 10 years. The blowers and drives are sized to meet current and future air flow demands (if the town decides to expand and add an MBBR) by only replacing the blower impellers without needing full equipment replacement.

Project Considerations

Land Constraints

One of the biggest complexities was finding a spot for the new facility outside the floodplain. The three site options were next to an airport, which required extensive work with the FAA to show the location and layout of the lagoons and demonstrate that they would not impact the airport in any way.

Planning for the Future

From the climate to the rivers, many locals believe their growth spurt will happen in the next 10 to 20 years. So, the plant design not only accounts for future treatment capacity but also includes features and functions to accommodate increasing demand. For example, if the town chooses to extend sewer service to the neighboring residential community, the connection can easily be made to a stub-out into the headworks facility.

When Plains needs to expand, the system includes piping that could connect to a future Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (MBBR). An MBBR allows for future expansion if ammonia limits are introduced into their MPDES permit or to accommodate growth beyond the capacity of their three-cell lagoon system.

Project Funding

Even though this project received a FEMA $5.1M pre-disaster grant, the design team watched project costs closely. This grant is typically given to coastal states to prepare for natural disasters. FEMA recognized that Plains could have experienced a catastrophe if they left the plant where it was. The potential for disaster increased with each flood, so the design and construction schedule project ensured this project was online as quickly as possible. Plains reported that this project was the first one where they weren’t waiting for the engineers to finish.

Equipment Selection

During preselection, costs were weighed throughout the equipment’s entire life cycle, including the aeration equipment, blowers, and UV system. Frequently, the lowest capital cost option has more operational expenses than those that cost more on the front end. Keeping operating costs low is especially important for Plains, as the costs will have to come out of their pockets once the financial grants are gone. This can be a significant burden to their ratepayers.

Connecting Existing and New

Nearing the end of construction, the tie-in to the existing force main – first for influent, then for effluent – needed to be carefully coordinated. The new plant needed to be operational before influent could be routed to it. The blowers were on site and scheduled for start up the week after Thanksgiving—not an ideal time to commission a WWTP and get the biological process started.

The influent was sent to the new WWTP on November 7 so the contractor could begin connecting the existing force main to the effluent force main of the new plant and constructing a connection from the existing force main to the existing outfall. This connection would allow the new plant to use existing infrastructure to discharge from the existing outfall. At the same time, work on decommissioning the old plant began. Everything was going well until the Monday after Thanksgiving, when a snowstorm delayed the blower start-up until the first week of December. Fortunately, the storage in the new lagoon basins allowed 28 days of aeration before discharging. The town’s wastewater flow was retained in the new lagoon basins for almost two months before discharging. At no time did the new plant violate the Town’s discharge permit.

Learn More About Our Wastewater CapabilitiesRelated Projects

Butte-Silver Bow Wastewater Treatment Plant MBR Upgrades

Morrison-Maierle developed a cost-effective, efficient wastewater treatment plant in Butte using advanced technologies that minimized environmental impact on a nearby Superfund site.

Deer Lodge Wastewater Treatment Plant

With several physical constraints and obstacles to factor into this project, the City of Deer Lodge now has a long-term, cost-effective solution for its wastewater treatment.

Four Corners Wastewater Treatment Plant

Four Corners Wastewater Treatment Plant